Put your growth on autopilot

GrowSurf is modern referral program software that helps product and marketing teams launch an in-product customer referral program in days, not weeks. Start your free trial today.

Founded in 2012, Matt Salzberg, Illa Papas and Matt Wadiak were on a mission to make thoughtful home cooking more convenient and accessible to busy professionals and families. The early concept-company reimagined how food was distributed, prepared and consumed then aimed to develop a sustainable food option that was affordable and health-conscious.

When the three friends from Long Island City quit their 9-5’s to launch the meal kit company, a path to Blue Apron's success was unclear. With limited experience in the food industry, Blue Apron’s marketing strategy would need to bring bounties to the table.

The team started out fulfilling orders by hand from a small commercial kitchen on the east coast. Blue Apron provided pre-portioned, pre-packaged meal kits, delivered to your door. The delivery included your choice of protein and all the ingredients needed to complete the chef inspired recipe provided. The entire operation was being funded by family and friends.

By 2013, the Blue Apron meal kits were available to 80% of the country, delivering over 100,000 meals per month. Increased demand meant there was an immediate need to scale up fulfillment and distribution to maintain momentum. Blue Apron raised $50 million in investment by the end of April 2014 to sustain their growth at a $500 million valuation.

In 2014, Blue Apron reported $77.8 million in net revenue and total operating expenses of $108.6 million, with 13% going directly into Blue Apron’s marketing strategy. The company was hot to acquire new customers and their bank accounts were being stocked to do so.

Blue Apron’s success was seemingly a pinnacle in 2016 when the company reported a profit of $3 million. With little competition, numbers had skyrocketed to $795.4 million in revenue. Unfortunately, the rise to the top was short lived. Only a year later, Blue Apron claimed $52 million in losses. The market had become saturated with new meal-kit providers like EatFresh offering similar services.

Blue Apron needed to move quickly to keep up to competitors by ramping up customer acquisition and retaining existing members who now had other options. With $35 million in operating costs, Blue Apron’s referral program was an aggressive move that ate more than its share of their profits.

Once a well intentioned startup focused on global sustainability and consumer convenience, Blue Apron has become a cautionary tale. In this article, we examine how you can protect your referral program from becoming a recipe for disaster.

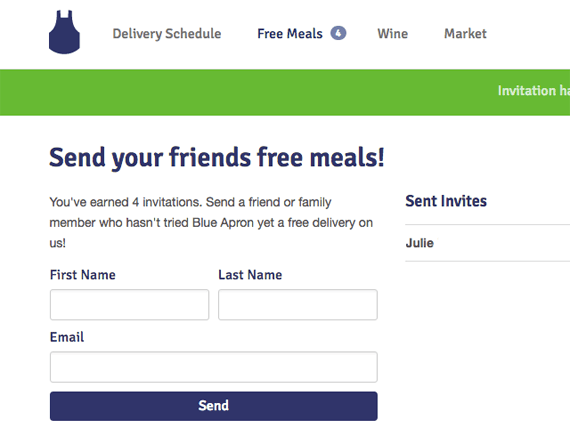

Want to try Blue Apron? Free food. Have a friend that eats? Perfect, free food. Every new customer of Blue Apron received a free introductory meal kit. The referral program incentivized sharing their meal kits with your friends and family by serving up more free meals. When existing Blue Apron customers referred potential subscribers, both the referrer and the referred person received a free box of food. Each subscription was eligible to refer 4 friends.

Customers referred to a company by a friend or family member are 4 times more likely to become customers. Referral marketing operates as an extension of trust. Think about it, if someone you know determines a product has value and they want to share it with you, you're likely to take interest. Not that free food being delivered to your door is a hard sell.

The referral program consumed 14.5% of Blue Apron's marketing budget, amounting to $35 million dollars. In the eyes of Blue Apron, it was money well spent. Their customer growth spiked and return was measurable. 34% of new customers came through their referral program. Blue Apron’s referral program was one of the most successful of all time, until it turned into one of the widest scale failures in referral marketing.

After a user spent up all Blue Apron’s introductory offers, they were given the option to start paying for the service or cancel their subscription. If they cancelled, as many did, they received emails inviting them to return with more promo codes and free food. Many users abused this system, even creating new accounts with another phone number or email account.

By this point, new meal kit companies like EatFresh had arrived in the US offering new recipes, similar referral programs and discounts on products. This made it too easy for consumers to take advantage of this open-handed referral program strategy, rendering Blue Apron’s LTV (customer lifetime value) almost nil.

Not all referral programs are created equally. They range from 10% off coupons to free trials and additional pro-bono products. Blue Apron chose the latter, assuming the $35 million they were spending on giving away free food would not only expand their customer base but retain them.

But what happens when the new kid on the block is also giving away free food?

What happens when customers that have been conditioned to expect free products see their incentives drying up?

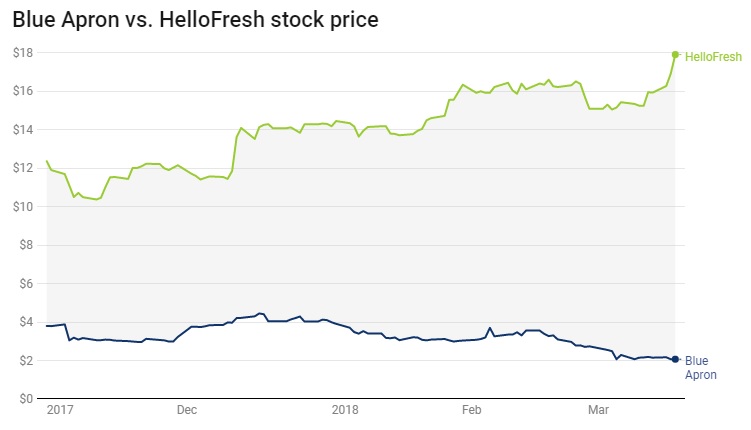

Blue Apron learned the hard way that trust isn't always a two way street. Customers were quick to switch to other meal kit companies offering similar introductory benefits. Blue Apron’s referral program was simply too generous. Their customer acquisition cost (CAC) was too high with no guarantee of consumer loyalty in a flooded market. HelloFresh, second to market in the US, benefited from being next in line. Not only did they have to offer less free food, they calculated and planned out a much more manageable CAC.

Image source: Vox.com

It’s hard to understand how Blue Apron was unable to predict this when even their valued customers were able to do so. It's clear they would have benefited greatly from spending more time on their pricing strategy.

“I used Blue Apron since I was getting $20 off 3 boxes. As soon as I stopped getting it, I cancelled and within a week I got emailed another promo code to come back for two weeks. I did that again and now I have another promo code that's good for another 3 weeks.”

“I'm basically just paying $40 because at that price it's worth it with no intention of ever paying the full $60 dollars. How the heck is this company still in business?”

Blue Apron’s overconfidence in their product cost them their majority market share.

In essence, the referral program was a success.

It was generous, but too generous and people took full advantage. It’s hard to turn down free food. Blue Apron's referral program costs ate them alive.

It’s not always the best practice to give more than you receive. It’s simply not sustainable for the vast majority of companies. Blue Apron padded its customer base with people expecting free food in exchange for their subscription fee. After exhausting signup bonuses, users cancelled their subscriptions en masse. With competitors like HelloFresh offering similar incentives, the easy decision to leave resulted in an abnormally high churn rate for Blue Apron.

People love free things. People love free food even more. While offering free things can bring in new users (and customers), it can also attract non-ideal customers that will leave your service once the free incentives reach their expiration date.

Choosing the wrong referral incentives not only increases churn, but it lowers your overall LTV and can severely hurt your cash flow. When choosing referral program incentives, there are many factors to consider to prevent Blue Apron’s recipe for disaster.

Where is Blue Apron today, in the quarantine era?

Prior to the forced shutdown, many retailers were having a hard time competing with e-commerce companies. Now, in an ongoing era of restrictions, lockdowns and social distancing, it’s forcing many brick and mortar businesses to close their doors permanently.

While some savvy business owners might be finding ways to adapt to the changing landscape caused by Covid 19, the switch to online, on- demand, pandemic-proof services isn’t overnight and many companies simply won’t survive the new normal.

For struggling businesses already offering these services, March 2020 was an unexpected stroke of luck. With the pandemic panic, consumer behavior switched into survival mode. With people spending more time at home, Blue Apron has enjoyed the increased demand for meal kits. Covid 19 pandemic helped pump the brakes on Blue Apron’s rapid decline.

The company used the steady uptick of orders to try to improve their brand by offering specialized diets, chef endorsement, and even wine pairings direct from partnered vineyards.

Blue Apron managed narrow losses from $22 million in 2019 to $11 million just a year later. As infection rates continued to climb, so did their average order value. With an average of $61 per order and 15% more orders being received, Blue Apron’s LTV was up 22% - the highest since 2014.

While the company was able to find some silver linings in what was otherwise a tragedy worldwide, growth metrics plateaued and have already begun to drop off. The company blamed customer deceleration on its marketing cutbacks since the start of the pandemic, but we find that hard to believe.

“Product innovation remains central to our strategy and initiatives to drive customer attraction and engagement. We introduced more new products in 2020 than in any prior year, including the recent launch of our new recipe customization and additional ways for our customers to get more meals from us each week. Both product introductions were well received by our customers and contributed to growth in key customer metrics such as Orders per Customer and Average Order Value, as well as Average Revenue per Customer” -Blue Apron

Blue Apron isn’t alone in its post-pandemic decline, however. Netflix is beginning to see their growth velocity dwindle as vaccines become available and life returns to (the new) normal. During quarantine, the streaming service saw a surge in demand as tens of millions of people subscribed to the platform in search of entertainment. Many people feeling financially strained turned to the service in lieu of expensive cable packages.

Netflix expected growth to decline after coronavirus restrictions began to subside but figures fell below the company’s forecasted 2.5 million new subscribers and well below the 3.9 million expected by analysts.

“The state of the pandemic and its impact continues to make projections very uncertain, but as the world hopefully recovers in 2021, we would expect that our growth will revert back to levels similar to pre-COVID,” Netflix wrote in a letter to shareholders.

Not all companies that saw their business boom during the pandemic are expecting the same collapse in growth. Amazon said although the pandemic was receding in some markets it expected its sales and profits to continue to grow. 50 million people joined Prime during the pandemic, accounting for an approximate 33 percent growth of the base, profit was $8.1bn, up from $2.5bn a year ago.

Amazon Prime isn’t as vulnerable to the same downturn as other companies. This is at least partially due to its integration into a marketplace that offers nearly anything you can imagine. Either way, things have never looked better for Amazon. Growth is expected to remain steady and it is forecasted by 2026 Amazon founder and former CEO of Amazon, Jeff Bezos will become the world's first trillionaire.

In the world of economic crises, there are winners and there are losers. As we look towards a post pandemic world Blue Apron can no longer rely on the necessity for their product created by a pandemic to stimulate their growth. Perhaps they’ll revisit their referral program one day with a new approach. Choosing the right referral program incentives can go a long way, even for a company that didn’t hit a home run at first bat.

If you're concerned about the costs of referral incentives, you can use our handy Referral Program ROI Calculator to pinpoint exactly how valuable a referral campaign can be for your company.

GrowSurf is modern referral program software that helps product and marketing teams launch an in-product customer referral program in days, not weeks. Start your free trial today.

The Reciprocity Principle, otherwise known as the Norm of Reciprocity, leans heavily on the most natural of human instincts.

Fitbit revolutionized a new industry of wearable tech, but how did they manage to get to their $9.7B valuation? Let's deep dive the Fitbit marketing strategy:

Learn why and how to choose an incentive for your referral program. Discover the best referral program incentives that will turn visitors into customers!